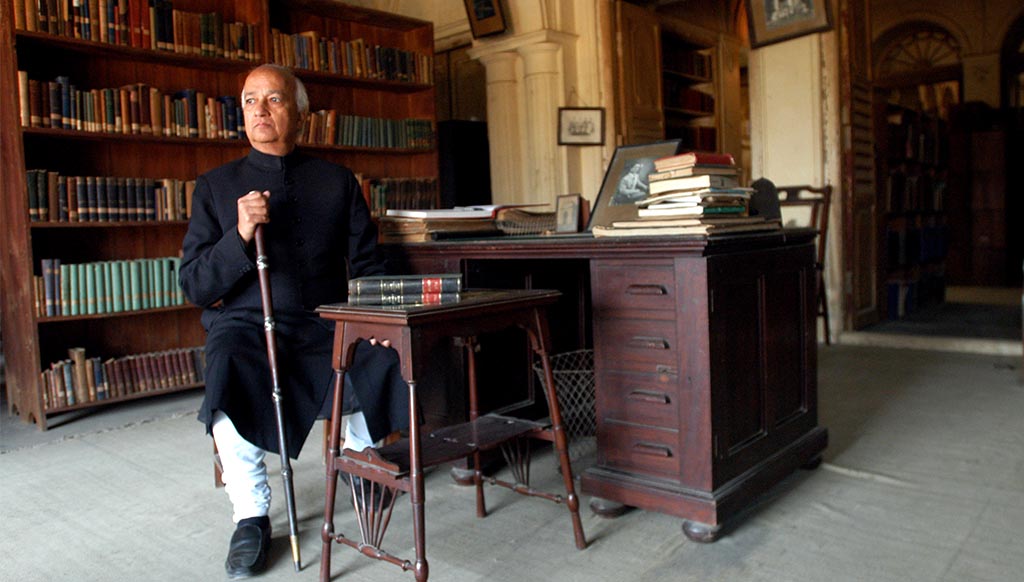

Mohammad Amir Mohammad Khan, the Raja of Mahmudabad holds forth on the little known aspects of Indian Royalty, and his family’s deep involvements with the country’s literary and cultural traditions, in this exclusive conversation with The Luxe Café

Opulent palaces, spectacular jewels, vintage cars and resplendent finery—if those are the only things you think royalty is all about, you haven’t met the right kind of Raja. On a crisp winter morning in Lucknow, with the wind chilling us to the bone and making us hug ourselves close, we enter the gates of the Mahmudabad Palace, a majestic property that speaks in muted tones of past glories, elaborate titles and great prestige.

In one of this erstwhile Palace’s rooms—a veritable cave of treasure, albeit the kind that’s bound in covers: history, philosophy, mathematics, astrophysics, religion, literature, poetry and so on and so forth— we sit face to face with royalty: Mohammad Amir Mohammad Khan, fondly called Suleiman Bhai, and formally still known as ‘Raja sahib’, the Raja of Mahmudabad. Dressed against the cold in a long gown, which he informs us is the Moroccan Djellaba, the Raja is a distinguished-looking man with aristocracy written all over his face, and a little something else—kindness, perhaps, and serenity, with a touch of poetry. And poetry flows abundantly in our conversation—Persian and Urdu couplets at appropriate moments—even as he quotes, with equal ease, verses from the Quran and shlokas from the Ramayana.

An articulate man, there is an air of old world charm about him, his manner reminding one of a bygone era and a culture that has all but vanished, a depth and sensitivity that is so rare to come by. And yet, even more strikingly, Mohammad Khan is a veritable historical text unto himself, his answer to every question wreathed in layers and layers of history. But he is quick to remind you that he is a mathematician, not a historian—a mathematician and a theoretical astrophysicist. A Raja indeed — possessing the boundless wealth of knowledge.

One does feel curious though, as to how, even in this day and age, he is still referred to as a Raja? And how did his forbearers get the title of Raja in the first place, considering that the royalty of Awadh is obviously associated with the title of Nawab? The answer begins long, long ago, in the annals of history.

“That’s a very good question,” smiles Khan. “You say many people wonder, but in fact many people don’t ask! Only some people do, and those people have thought about it and wondered. It’s interesting, because many of the existing Rajwaras in India, the Nawabs and all, they sometimes inadvertently call me Nawab. Because in their minds a Muslim is associated with the position of a Nawab and a Hindu is associated with the position of a Raja and Maharaja. And I don’t blame them for that. But they don’t know the reason.”

“Many of the existing Rajwaras in India, the Nawabs and all, they sometimes inadvertently call me Nawab”

“You see, when the Mughal emperor from Delhi sent Burhan ul Mulk as Nawab Wazir, the Nawab Wazir part got shortened to Nawab. This was a position similar to a Viceroy. But nobody took the trouble of saying Nawab Wazir all the time. So one after another, right up to Wajid Ali Shah, this entire line became the Nawabs of Lucknow. Wajid Ali Shah’s grandfather’s elder brother was the first king of Awadh, known as the Shah e Awadh. But the word Nawab was still associated with them. Later the British began emphasising, for their own ends, the importance of Awadh—essentially to break up the Mughal Empire.”

He pauses, to emphasise the point: “The Mughal Empire was actually the symbol of the unity of India as one understands it in those times. The throne in Delhi was therefore very important and the British wanted to displace the Mughal emperor, and weaken him before displacement as much as possible. So in Awadh they played to the ambitions of the Nawabs and encouraged them to declare themselves as King, which they did. And it was the British who recognised him.”

“It is said that when the emissary from Awadh went to the Emperor of the time—one of the lesser Mughals— the emissary put it in the most florid language. He said, if there were no King in Awadh, how would you then be the King of Kings?” He ends the episode with a flourish, the cadences of his voice adding drama to the narration. Our conversation is interspersed with such witty anecdotes, history unfolding as if before our very eyes. But we still haven’t reached the answer to the original question.

He continues, then telling us that the Shahs were also called Nawabs by people and so the title of Raja was meant for differentiation. Raja would be subordinate of the Emperor and of the Shah in Awadh. And then he reveals a fact that is utterly surprising, especially in how little known it is.

“A point that’s been concealed deliberately—or perhaps by oversight,” he emphasises, “is that at the height of the Mughal Empire, the Rajas and the Nawabs were not hereditary. None of them. I’m giving the biggest example: when Jaipur became a part of the Mughal Empire, the ruler was called a Raja. In addition to that, he was addressed as the Zamindaar. Do you know why? The Zamindaar was a tax collector and custodian, a representative of the king. So when someone referred to the Raja of Jaipur, they would call him Raja Mansingh, Zamindaar e Jaipur. It was not necessary for his son to be a Raja as well, though. It so happened that nobody interfered.”

“At the height of the Mughal Empire, the Rajas and the Nawabs were not hereditary. None of them.”

At this point, we are joined by Khan’s younger son, Amir, who is doing his PhD in History at Cambridge University, his father’s and mother’s alma mater. He steps into the narrative, adding to it. “The British began to structure and order the princes of India along the lines of British aristocracy—with one thing in mind. To (reward) those who had been loyal to them.”

But the case of Awadh was different. “Wajid Ali Shah took the court very seriously, raised and trained a royal army here,” says the Raja. “The British wanted a symbolic force, but he went beyond that; to the extent of inventing commands in Persian Urdu for the military drill. It was when Akbar came to Lucknow, though, that he created the talluqedars, in Awadh, in whom Wajid Ali Shah saw a wonderful opportunity to create a court.”

And finally comes the answer to our first question: “To our family, he gave the title Raja with a purpose. Because, he said to the Muslims who were being created Rajas, the majority of your subjects are Hindu. In order to create a bond with them, I will make you a Raja.”

Amir, his son, breaks into laughter at this point. “Oh, so this was the question half an hour ago?” He wonders out loud, making us all laugh. And then goes on to narrate an anecdote of his own. “Abba’s a mathematician, and I used to come to him for help with Maths, when I was in university. And it was always a mistake,” he chuckles, “Because Abba would decide that instead of helping me, he would talk about an entirely new direction of Mathematics! I would say Abba please explain this proof to me, and he would say, well that is interesting but have you considered this— and that! An hour and a half later I wouldn’t have any idea about what I originally wanted!”

The senior Khan protests mildly, genially, and then concedes defeat. “My brother in law says,” he tells us, smiling, “that Suleiman Bhai when you’re asked a question, you go round like an eagle in circles over the prey… until that circle finally shortens to the point. But it takes very long!” he grins broadly.

“I used to teach at Cambridge,” he reminisces. “I studied mathematics and also did research on theoretical astrophysics later. So when I was teaching undergraduates in Cambridge, they were very interested in how I taught them, but one day a kind of ‘delegation’ of them met me and said, it is wonderful that you take the time to do this, but you know we miss our dinner in the hall and we have to pay for the entire thing. It’s very expensive. So then I said I’ll take care.” He smiles broadly again. “So I confess that there is a certain kind of desire to expand on things.”

And that is understandable—inevitable too, for a man who is such a storehouse of knowledge and facts and ideas, he positively overflows with them. Take this, for instance: the story of how the Rajas of Jaipur got the title of ‘Sawai’.

“Sawai means ‘sawa’,” he explains. “One and a quarter. So it was during Aurangzeb’s reign that the Jaipur family came to be known as ‘Sawai’. A young man from the Jaipur family had trouble with Aurangzeb, initially a source of conflict between Jaipur and Delhi, but Jaipur was not successful.” The young man in question was Raja Jai Singh II, later known as Sawai Jai Singh.

“The man was brought to court, and Aurangzeb called him towards his throne and held both his hands in his own hands. And he said, what do you say now that you are in my hands? This very young man immediately answered: What greater honour could there be for me that I should be in the hands of the great emperor? Aurangzeb looked around and, because of the young man’s years, said in Persian: He is not just a man, he is a man and a quarter—Sawai!” He concludes with a dramatic flourish, “And this is how the title Sawai came into being.”

In a more philosophical vein, Khan goes on: “Now a lot of families have mythologised the past. I think that reality itself is so interesting that we shouldn’t mythologise it.”

He tells us about Abul Fazl and Faizi, among the Nauratans from Akbar’s court: “Abul Fazl was a great intellectual, a universal kind of man, who knew religious theory, was a poet and a thinker. He and his brother Faizi were geniuses. There is an exegesis—a tafseer of the Quran—written by Faizi, which is ‘benuqat’ (‘nuqta’ refers to the dots used in certain Arabic and Urdu letters, hence benuqat denotes an exegesis which does not make use of any of the Arabic alphabets that have ‘nuqtas’ in them— an astonishing feat). It’s amazing! Jeem, Zaal, Zey, Noon.” He exclaims, naming the alphabets that have not been used. “I think we have that exegesis in our library.”

“Now a lot of families have mythologised the past. I think that reality itself is so interesting that we shouldn’t mythologise it.”

The Raja’s eyes light up with indescribable rapture each time he speaks of the minds of geniuses and great feats of intellectual and spiritual endeavour. His mannerisms, cadences of speech and range of expressions are enough to hold the listener in thrall, almost like a wizard spinning spells right before your eyes. Someone from a distant dream—a man almost unreal.

At one point he puts up the hood of his Djellaba to give us a demonstration of the long, brown gown. And one can’t help but be reminded of Albus Dumbledore, the kind but powerful wizard created by JK Rowling.

Turning back to reality, we discuss with him the books in the famous Mahmudabad library. The Mahmudabad Library houses thousands of rare manuscripts and printed books and the estate is working on the preservation of manuscripts in collaboration with various international organisations and institutes.

“My (elder) son Ali, who teaches at Ashoka University, has been successful in getting a grant from the British library on our terms and conditions, which means, within the framework of the Indian law,” he explains. “There are people here visiting us at the moment, from various institutes, as there was a conference here funded by The Islamic Manuscripts Association, the Roshan Institute (University of Maryland) and people from the University of Maryland. There is Dr Fatimeh Keshavarz from Maryland, Professor Richard who was formerly director of the National Archives of France and also director of the Islamic archives at the Louvre, and Dr Jake Benson from Leiden University.”

All of these illustrious personalities are guest of the Raja, and he rises to have lunch with them. We are invited to have lunch with them as well, and this turns out to be a delightful, blissful affair as Persian, Urdu and English poetry flows headily, abundantly between us. Complete indulgence and intoxication for the mind.

Post lunch, we resume our conversation, and I bring him back to the subject of Mahmudabad library, asking him of the rarest, most precious manuscripts. “It’s very difficult to say because each time I look at a book I find something new in it,” he explains. “There are Qurans that are beautifully written, just to look at them—in the Kufic script and the Nastaliq, and the Taliq—it’s extraordinary.”

His son adds an important observation to this: “I think all (our forbearers) who collected books, manuscripts and all, never looked at it as acquiring something material. It was never an investment that we might be able to capitalise on in the future. It was looked at as access to knowledge. And so, depending on your stage of mind, a different book becomes precious.”

“All (our forbearers) who collected books, manuscripts and all, never looked at it as acquiring something material. It was looked at as access to knowledge.”

Khan explains further: “It’s very difficult to read manuscripts you know. You have to have time and devote yourself to reading them—sometimes they are fragile and so on. But otherwise there are books on poetry— there’s Nizami, Hafez, Saadi, Rumi. A large collection, we’re still going through it. Every time we look at it there’s something novel.”

What’s more, there’s also a large collection of poetry by their forbearers, as Amir informs us. But they’re not in the form of books. “It’s either marsiyas, or salaams or ghazals. And some books, such as the book ‘Jawn, Martyr of Karbala Lamented’ by Raja Mohammad Amir Ahmed Khan have been republished recently with critical introductions. Hazrat Jawn was one of the companions of Imam Husain,” he elucidates. “It was interesting that Jawn was chosen as the subject of the marsiyas because he was an Ethiopian former slave, an elderly man over 80 years old, who had got his freedom in order to fight as a free man alongside Imam Husain. And so it is a tradition in our family that when we recite from the mimbar (raised platform) during Muharram, we recite the poetry of our forbearers.”

Marsiyas and salaams, poetry in the form of lamentations and elegies, are an integral part of Muharram, a deeply spiritual month for Shia Muslims wherein they mourn the supreme sacrifice of Imam Husain. More importantly, it is also a huge part of the syncretic heritage of Mahmoodabad, where the majlis gatherings are not just an important spiritual activity, but also a literary and cultural one. The marisyas, the soz and salaams beautifully blend the poetic and musical traditions of Hindus and Muslims, for they are recited in the Indian classical ragas and raginis.

“I believe Muharram is a very important practice which helps in keeping this culture alive,” emphasises the Raja. The soz, the marsiyas are recited in the Indian classical ragas and raginis. However it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to do it—the patronage is gone. So there is no confidence in those who practice these arts that they would have a livelihood permanently and in future. There is a doubt in their minds, you see, and that makes them go away from the art. The point is, that food and music require our interactive patronage. A cook cannot cook perfectly, cannot improve his skills, cannot bring in other flavours to enhance the food unless the person who eats tells him.”

“These traditions, the musicality, reflect something incredibly important, particularly at a time when we see a certain kind of idea of India emerging. And that something is the multiplicity of confluences that went into creating the particular repositories of culture,” highlights Amir. “So we may sing elegies in memory of the martyrs of Karbala but we sing them in terms of Indian ragas and raginis. And each one of the raginis is a deity in the Hindu pantheon! It is Hindustani classical music. Wajid Ali Shah, the King of Awadh, was a great aesthete when it came to music and dance. His personal involvement in the rehabilition of Kathak is regarded even to this day. He was a very, very cultured man and a poet. But unfortunately the image that has been presented of him is that of a man who was decadent.”

“We may sing elegies in memory of the martyrs of Karbala but we sing them in terms of Indian ragas and raginis. And each one of the raginis is a deity in the Hindu pantheon”

So how does the estate of Mahmudabad promote these now? He accepts that the legal complications and controversy surrounding his property, because of the amendments introduced by the government in the Enemy Property Act with retrospective effect, put material constraints on all that he would like to do. “It’s very difficult for me to do all that because I have material constraints. And I feel that –the government may vehemently deny this—but somehow they misread us on the one hand and also at the same time they wanted symbolically to burden me with something for which I was not responsible, which was my father’s involvement with the creation of Pakistan. In order to symbolically punish him—my father is gone and he could not be directly punished by them— I am being used as a surrogate for him. Which is completely wrong because I have always been an Indian, never a Pakistani. My mother was never a Pakistani, always lived an Indian, died an Indian. One of the lawyers in Supreme Court said, the late Raja helped the creation of Pakistan and this Raja who’s sitting here is trying to create another Pakistan!”

And all this, despite the fact that he is also a former legislator, having served as MLA from the Congress twice. A Muslim politician who used to begin all of his speeches with a shloka from Ramayana—as his son informs us.

“In order to symbolically punish him—my father is gone and he could not be directly punished— I am being used as a surrogate for him, which is completely wrong because I have always been an Indian.”

He continues, “Mr Jailtey’s speech in the Rajya Sabha shows how they are trying to make me fight a court case for my rights—a right that I won unequivocally and unconditionally and completely in the Supreme Court (in 2005) and had been handed over everything.”

“So now with our limited resources, we promote cuisines, cultural and poetic events, the publication of books, and keeping alive the syncretic culture through Muharram,” he says.

The syncretism of the Indian civilisation is something he believes very strongly in, and is very vocal about. Ask him about the idea of India, and this is what he says.

“This is a very difficult question. The greatness of the Indian civilisation lies in one very distinctive feature that it has absorbed so many influences and not rejected any of them and has actually, in a very gentle form, influenced them not to grow in one direction, but in multiple directions, whatever way they originally came from. So Islam became a sort of Indian inflected Islam in the way it was expressed or practiced. I do not know—people talk of composite culture— I don’t know quite what that means, but I do know this, that cultures influence each other, that they are not like water-soluble dye which just goes into water and vanishes. They are the insoluble dyes that retain their colours in the water in which they flow, have their own dynamics and their own flow. Without mixing with the water, but being a part of that system— being a part of that water. Syncretism does not mean that Islamic principles are diluted or compromised. That, to my mind, is the strength of it. And that should be the strength. If it’s not, if that dye is being transformed into one which dissolves, it will be a loss for India.”

“India is a continent in itself!” He exclaims fervently. “People want to consider it as a nation! I consider it a continent, which is much greater than a nation. You see? And there are cultures and languages and ideas and cuisines and thoughts and religions and sects and subsects and so on. The one wonderful thing is that there has rarely been any attempt to impose uniformity. Uniformity can be terrible. It can appear a regimentation where you just slot everyone into one and everyone goes down the same line. For me, the love of the country is not an abstract concept. It’s not just saluting a flag or singing the national anthem—these are abstract things. For me, the love of the country is the love of those who live around me.”

And he presents an example of this syncretism in personal life as well, for his wife is from a renowned Hindu family of Udaipur, the daughter of former Foreign Secretary, Jagat Mehta. “I do not think that ideas, beliefs are like political divisions and countries in the world where you draw boundaries. It is something much beyond that. There are values and beliefs which transcend religions and those may act as bridges to travel from one to the other. People may call it submission, or coming together of two cultures, but this is only a name. The essence is that the core remains.”

“For me, the love of the country is not an abstract concept, not just saluting a flag or singing the national anthem. For me, the love of the country is the love of those who live around me.”

The entire heritage of Mahmudabad represents the syncretic culture of India, says the Raja, but with an important distinction. “By being rooted in our own tradition. Not through the wishy-washy diluted kind of thing. By being rooted in this tradition, I recognise the importance of the other traditions—and the fact that our roots somewhere are intertwined. As an entity above the ground, I am separate. But I’m intertwined with that earth—with this land—not just the soil. The people, the thought, the philosophy. And we must never allow this to die. Because this is the richness which God has endowed us with.”

Adds his son, “There is no such thing as the clash of civilisations; there is no Muslim culture and Hindu culture. For religion to become a part of the fabric of societies, it can’t be isolated, or try and retain some kind of purity. There are many traditions we have here which can be traced to other religious traditions. So my mother, yes, she was from a non-Muslim family, but many of the traditions of their family mirror the traditions of ours. It was quite natural for her because the roots were the same.”

Those common traditions include linguistic influences, for instance. “Take a look at the language of Mewari. Mewari has a huge number of words that are derived from Persian. In terms of levels of politeness, the way in which you speak to your elders with respect, is actually using Persian terminology,” explains Amir.

“I think the concept of morality is a universal concept. And the awareness of that existed in her family as well, of course,” interjects the Raja emphatically.

He points out that even one of the Sikh gurus wrote Persian poetry. “Language is a vehicle and a carrier not just of thought, but it has roots somewhere and has evolved through a certain religio-cultural system, to come to mean what it is.”

So what are the literary and cultural pursuits of a modern day Raja, I ask him. He tells me about discussions and conversations with people of erudition, and how he longs to have more of those.

“There is much that I read,” he says. “And talk to people as much as I can. There’s a great dearth of individuals who are interested now in these kind of pursuits. There’s a young man, a close relative of Maulana Jalauddin Abdul Matin, popularly known as Matin miyan, who was a wonderful sufi and aalim from Farangi Mahal —though he would have objected to the word aalim! He was very close to me. One of his nephews is there and he imbibed quite a lot from him, so I look forward now to interacting with him as I interacted with Matin miyan. There are literary figures—Sharib Rudolvi sahib, Anees Ashfaq sahib, Husain Afsar sahib—and it’s a pleasure to talk to them. But I miss Matin miyan. I miss the kind of company which my father had when he used to visit India, and I search that. On certain days, I’m more inclined towards reading on mathematics, mathematical physics—it’s hard because it needs devotion, concentration, single mindedness—none of which I have, and which I try and collect together and put in an effort to do it. So I alternate between mathematics and mathematical physics, theoretical astrophysics, to literature. Theoretical astrophysics is mathematical physics, you see, with the difference that it talks about the universe and the stars and galaxies.”

“I didn’t move around amongst people of my own age! I was invariably with people who were 15, 20, 30 years older.”

“The things that I do miss very much are the people, and of course that’s inevitable. So many of them have gone. And the reason is because I didn’t move around amongst people of my own age! I was invariably with people who were 15, 20, 30 years older.” And that, perhaps, is what has made him what he is, I think aloud. “Exactly, you are right!” he agrees. “I yearn for their company. So I close my eyes and I see in this very room where we are sitting, poets, writers, ulema…” he trails off wistfully. And you can just see him sitting here surrounded by them; see the room come alive with sublime poetry and deep intellectual ruminations.

More treasures of tales from the Raja’s life spill out before us as we speak.

Watch this space for the uncovering of more secrets in the second half of this two-part series on the life and loves of the Raja of Mahmudabad.